Wikisage, the free encyclopedia of the second generation and digital heritage, wishes you merry holidays and a happy new year!

Never Split Tens (movie prospectus)

Never Split Tens (movie prospectus) presents the formal prospectus of the movie version of the biographical novel of blackjack game theorist Edward O. Thorp by writer Les Golden by the same name, published in 2017 by Springer International Publishers (ISBN Number 978-3319-63485-2). PROSPECTUS

Feature-Length Motion Picture “Never Split Tens”

Additional information is provided at en.wikisage.org/wiki/Never_Split_Tens

Summary

Offering: Feature length motion picture Production Budget: $10 - $15 million Market: Domestic and foreign theaters, rental, download, television, and ancillary media. Anticipated Rating: PG-13

Federal Tax Policy: By U.S.C. 181, investment in a motion picture filmed in the United States is 100% tax deductible for the investor in the year of investment.

“Never Split Tens” aka “Doubling Down” is a feature-length motion picture (“Motion Picture”) based on the true story of Edward O. Thorp, an M.I.T. mathematics professor who developed the card counting system for the casino game of blackjack which revolutionized the casino industry. Collateral Appendix A provides the “tagline,” “logline,” and synopsis of the Motion Picture.

The screenplay writer is Les Golden. The First Draft of the screenplay is completed and it has been registered with the Writers Guild of America-West, with registration number #1505108. The copyright is held by Mr. Golden. He is uniquely suited to write the play as both a professional card counter and gambling columnist, probability and statistics professor, and writer, actor, and stand-up comedian. Appendix B provides Mr. Golden’s brief biography.

Leslie M. Golden and his associates (“Producers”) seek capital contributors (“Investors”) to fund a portion of the estimated production budget of $10 million to $15 million on a profit-sharing basis. Investment is also sought from a casino/resort where many of the location filming will occur in return for marketing considerations, and product placement. The Producers’ goal is to achieve at least a 120% return on investment.

Gambling is a major American industry and many successful motion pictures have been made on the subject. A thorough quantitative analysis of revenue history of motion pictures provides a strategy to effect a financially successful venture. Rentals and sales through electronic media complement the theater box-office revenue stream.

INVESTMENT IN MOTION PICTURES IS A HIGH-RISK VENTURE. NOTHING IN THIS PROSPECTUS SHALL BE CONSTRUED TO IMPLY ANY GUARANTEE OF A RETURN ON THE INVESTMENT TO THE INVESTOR.

The entertainment attorney for the Producers is Jay B. Ross & Associates, Chicago:

Jay B. Ross & Associates 840 W. Grand Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60642 (312) 633-9000 jay@jaybross.com

Producer Representation

Producers represent and warrant that Producers have the full power and authority to present this Prospectus; Producers are the sole proprietor of the Motion Picture. No third party is entitled to compensation with regard to revenues received as a result of the production of the Motion Picture including, without limitation, the United States government; Producers have not granted or assigned any rights in the Motion Picture to any person or entity; the Motion Picture is original to Producers; the Motion Picture has not been published in whole or in part by any other source; the Motion Picture does not infringe upon any copyright, trademark, patent or other intellectual property right; the Motion Picture does not invade the right of privacy or publicity of any person or entity; the Motion Picture does not contain any obscene, indecent, libelous or scandalous matter; all statements that are asserted in the Motion Picture as facts are true or based upon reasonable research for accuracy and, to the best of Producers’ knowledge, nothing contained in the Motion Picture would cause injury, damage, or other harm to persons or property if used or followed in accordance with the content of the Motion Picture.

For each representation and warranty made by Producers in this clause that is based on the best of Producers’ knowledge, Producers shall employ due diligence during the term to monitor and verify compliance and accuracy. Producers hereby indemnify and hold harmless Investors, their parent and subsidiary entities, officers, directors, equity holders, employees, agents and representatives (together, the “Indemnified Parties”), if any, from and against any costs, claims, liabilities, expenses or damages, including, without limitation, attorneys’ fees, disbursements and court costs, that the Indemnified Parties may incur or for which the Indemnified Parties may become liable as a result of a breach of any of these representations, warranties, and indemnities. These representations and warranties will survive the termination of this Prospectus and may be extended to third parties by the Producers.

Investment Offering and Investment Goal

The investment goal of the Producers is to obtain at least a 120% return on investment for the Investors. By comparison, the 2006 motion picture on a similar subject, “21,” earned total gross revenues of $158 million on a production budget of $35 million, a net 350% return.

Producers seek $5 to $13 million in private investment capital (“Investment Funds”) to finance the production of the Motion Picture. The total production budget of the Motion Picture is estimated to be $10 to $15 million. Additional sources of funds are detailed in Section 6, Business Plan.

All Investment Funds will be placed in a segregated interest-bearing escrow account which, unless otherwise agreed, may not be drawn upon until and unless:

1. the entire sum has been secured and deposited into the escrow account, 2. reputable international motion picture distributors are attached, 3. all Investors have been notified by Certified Mail that the entire sum has been secured and deposited into the escrow account and that it may begin to be spent on production of the Motion Picture.

Investors obtain a return on their Investment Funds in two stages, initially from the Producers’ Net Revenue and subsequently from the Net Profits. (These terms and others are defined and elaborated upon in the glossary of Appendix C.) As it accrues, all of the Producers’ Net Revenue is paid to investors until the sum equals 115% of their principal investment. This 15% “preferred return” figure exceeds or equals the figure paid by most producers.

Once Investors have received an amount equal to 115% of their Investment Funds, they shall be paid 65% of the Net Profits (see Glossary), if any, pro-rata based on their Investment Funds. The remaining 35% of the Net Profits will be retained by the Producers to pay all third-party participation (see Glossary), including directors, principal actors, and writers. This is a more liberal disbursement than the industry standard of a 50/50 split of the additional net profit disbursement.

The Investors’ share of the Net Profits shall not be reduced as a result of these payments or any other purpose.

Agreements between Producers and Investors shall be developed between Jay B. Ross and Associates, attorneys for the Producers, and the attorney of choice of Investor. Therein, the Investor will be able to structure the agreement to attain his tax and investment goals, including but not limited to establishing limited partnerships or corporations, trusts, and location shooting.

Gambling and the Gambling Movie Genre

The Gambling Industry

By many measures, gambling is among the top “industries,” both in the United States and internationally. This reflects the apparently innate desire of human beings to take risk for both enjoyment and as an attempt to gain riches. The proliferation of state lotteries, which is simply the legalized (that is, taxable) reincarnation of the Capone-era numbers racket, casinos, and internet gambling attest to this drive, along with other types of wagering such as sports betting, both legal and illegal, other forms of illegal wagering such as office pools, neighborhood bookmaking, and home poker parties, horse racing, and bingo parlors and bingo nights at fraternal organizations and retirement communities.

A survey conducted by the Gallup organization for Psychology Today magazine showed that nearly 1 in 4 American men and 1 in 8 American women can be expected to gamble in some way on the Super Bowl (Ref. 1), with documented as opposed to illegal and office betting at $100 million (Ref. 2), similar to the amount bet on the Kentucky Derby (Ref. 3). Furthermore, according to the report by the federal Commission on the Review of the National Policy Toward Gambling, two-thirds of all Americans have gambled in one form or another (Ref. 1). Individual state statistics show that many Americans bet 1% of their income on state lotteries alone (Ref. 4).

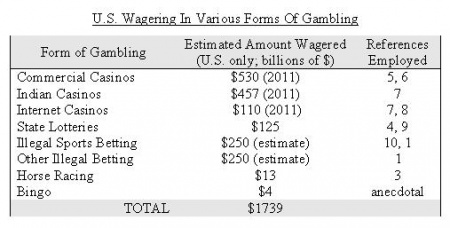

Gambling occurs in casinos, sports betting, racing, on the internet, and in bingo games. Much of the gambling is illegal, particularly in sports betting. The table summarizes estimates of the amount of money wagered in the various forms of gambling. The sources upon which these estimates are based are provided in the references at the end of the Prospectus.

It is important to note that the internet gambling portion of these wagers may soon triple. Before passage of the 2006 Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (“UIGEA”), the United States had been the dominant internet gambling market in the world, accounting for 50% of global Internet gambling revenue in 2006. Since the passage of UIGEA, Europe has become the dominant region, accounting for 44% of global revenue, followed by Asia (25%) and the U.S. and Canada (24%). It is expected that the domestic market would resume the dominant position if UIGEA is repealed (Ref. 7).

We find that at least $1.7 trillion is spent on gambling by Americans each year, an astounding total. Gambling, and by implication, fascination with gambling and those who gamble successfully, is an undeniable and significant aspect of human nature. The 2012 gross domestic product, the total amount of domestic production of all goods and services, is approximately $15.6 trillion. Although a disproportionate amount is wagered by “high-rollers,” professional gamblers, and those with gambling addictions, these figures demonstrate that the amount of money Americans spend on gambling in its various forms is at least about 11% of the GDP, about $1 for every $9 generated by the domestic American economy!

This estimate was in fact confirmed by the 2011 report of the American Gaming Association. Sixty million people, one in every four adults, visited a casino in the thirty-eight states in which casinos are legal and their wagers account for nearly 1% of the national economy, $1.6 trillion. (Chapman, Steve, “Freedom to gamble,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 2013, p. 25) The nature of the game of 21, which is prominent in the Motion Picture, is discussed in Appendix D.

The Gambling Genre of Motion Pictures

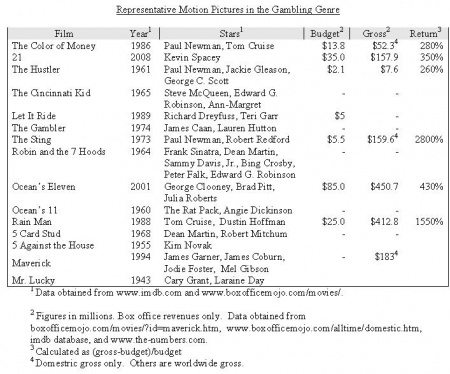

It is not surprising, then, that gambling is one of the most popular topics for motion pictures. More than 125 titles related to gambling have been produced and distributed internationally. Many of Hollywood’s biggest stars have been attracted to the genre to be cast in lead roles, including Paul Newman, Robert Redford, James Caan, Tom Cruise, Richard Dreyfuss, Edward G. Robinson, Dustin Hoffman, George Clooney, the Rat Pack (Frank Sinatra, Peter Lawford, Joey Bishop, Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin) both as a group and individually, Bing Crosby, Peter Falk , Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster, James Garner, James Coburn, Cary Grant, Robert Mitchum, Angie Dickinson, Julia Roberts, and Steve McQueen.

The lure of gambling has enabled some of these motion pictures to become blockbuster successes (gross revenues exceeding $100 million). Among individual motion pictures, the James Bond series of films incorporates casino gambling as an essential plot element, the Maverick television series and the motion picture of the same name featured gambling, and the motion picture Mr. Lucky was turned into a television series.

The table provides budgets and grosses for motion pictures in the gambling genre for which production budgets and gross revenue figures could be obtained. The return is calculated in percent as (gross-budget)/budget x 100. Some notable gambling motion pictures for which these figures are not available are also listed.

Estimated Production Budget

The production budget of a motion picture is determined by an industry-standard mode of budget analysis, referred to as “line production.” A producer reads the script line-by-line, determining the costs incurred by the creative personnel, and sets, locations, props, special effects, and other elements of the motion picture. Line production distinguishes four types of expenses, “above the line” items such as salaries for actors, directors, and other creative talent, the “below the line” items incurred in production, post-production costs, and other items such as insurance and contingencies. The detailed line items are summarized in a “Topsheet.”

The line production analysis for the Motion Picture was obtained using the widely-used Entertainment Partners’ Movie Magic Budgeting software as applied to the script for the Motion Picture. The corresponding Topsheet for the Motion Picture is provided in Appendix E with rounded figures.

The result is an estimated production cost of $9.9 million. Because this estimate is based on the First Draft of the screenplay, the production cost determined by this line production may differ for that employing the actual shooting script. Substantial differences are not anticipated. The $9.9 million includes an item of $5,750,000 for the principal actors, in particular, $5 million for three star actors in principal roles. Negotiations with theatrical agencies for use of the star actors may increase this amount to an amount that cannot be established before final casting. Among available star actors, the Producers will seek to cast those that will minimize this additional cost.

The Producers will seek to reduce costs in other ways. The script does not require the expensive night time filming resulting from using powerful lighting equipment and overtime pay schedules, rather employing so-called “day for night” filming in which a night ambiance is simulated cinematographically, it utilizes neutral venues for location shooting, and the Producers may seek to contract with star actors to receive profit-sharing compensation in lieu of large upfront salaries.

The Topsheet does not include tax incentives, production rebates, and other credits that film companies obtain based on the U.S. states in which actual filming occurs and negotiations with production companies. Because of the state of the national economy, such incentives, rebates, and credits can be significant. For example, as noted, Illinois provides a 30% tax rebate on production costs for Illinois shooting, which the Producers can sell for typically 88% to 93% of cash value (Ref. 11).

Based on these various considerations, the Producers therefore estimate the final production budget to be between $10 and $15 million.

This estimated budget is significantly less than the mean production budget for motion pictures produced in the years represented in Figure 1 below in Section 8, Production and Revenue Analysis and Considerations. This results from several factors, most notably the lack of special effects, animation, and action sequences, which can add more than $100 million to a budget, filming domestically, and the use of locations rather than sets.

The Producers may deem that a contract for a star actor is best achieved by a back-loading clause, in which the actor would earn a fee as well as a percentage of the net revenue earned by the Motion Picture. Incorporating a back-loading clause reduces the Production Budget. In this case, the agreement described in Section 3, Investment Offering and Investment Goal, between the Producers and the Investors would need to be altered and the Investors would be so notified. This notification would include providing the Investors the option to obtain a full refund of their investment. Back-loading results in a reduction of risk but is accompanied by an expectation of lowered reward, all other factors equal.

Business Plan

Production Budget Generation

Because no special effects, animation, or action scenes are involved, the budget for the Motion Picture, including two to three A-list actors, is estimated to be $10 to $15 million, as discussed in Section 5, Estimated Production Budget.

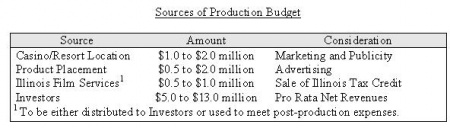

The Production Budget will be generated from Investors, a sponsoring casino, product placement fees, and possibly sale of Illinois tax credits. The minimum investment from Investors will be $50,000 (“Unit Investment”). No more than one hundred (260) Unit Investments will be sought from Investors (see table below), so that no dilution of interests will occur. The Investors will receive a pro rata share of profits in return for their investment as detailed below.

Because both the subject of the Motion Picture and many of its scenes involve casinos, it is advantageous to form an investment relationship with a casino in the production of the Motion Picture. In return for partial funding of the projected production cost of $10 to $15 million, the casino would obtain numerous marketing considerations, as detailed in Appendix F. Scenes to be shot in the casino/resort facility are detailed in Appendix F.

The Motion Picture has more than two dozen opportunities for product placement. These include a restaurant chain, convenience store chain, motel chain, automobile manufacturer, cigarette manufacturer, television manufacturer, ice cream manufacturer, rice packager, coffee manufacturer, box candy manufacturer, breakfast cereal manufacturer, orange juice bottler, brewery, liquor distributor, and winery. In addition, specific firms such as Metropolitan Life Insurance, Texas Instruments, IBM, Mars Candy Company, Milk Bone dog treats, and newspapers, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Boston Globe, are explicitly mentioned. The common stocks of several publicly traded firms are the subject of one scene. Product placement is attractive to manufacturers for many reasons. The products are perceived by the viewer to be chosen by the star, thus receiving an implied endorsement. The total number of viewers increases as the motion picture moves from theatrical distribution to the sales and rentals and electronic media. Third, the products are shown in the context of the show and cannot be ignored. Product placement, in addition, provides manufacturer the possibility of joint marketing with motion pictures that appeal to the manufacturer's target market audience. In the Motion Picture, the target audience for automobiles and various consumables such as cigarettes, coffee, beer, wine, and liquor overlaps significantly with the expected demographic for the Motion Picture. The fee (as opposed to receipt of free products or a mutual advertising campaign) for single product placements in motion pictures varies widely from $100,000 to millions of dollars. The Producers will enlist the services of established product placement firms such as Motion Picture Magic to maximize this source of the Production Budget. The corporate clients of these firms typically invest once a motion picture has obtained one or more distributors. These fees are expected to generate between $500,000 and $2.0 million toward the Production Budget. The sources of the Production Budget are summarized in the table.

Revenue Generation

Revenue will be generated by distribution in domestic and foreign theaters and to non-box office outlets. These include DVD/Blu-ray, Video-on-Demand, Electronic Sell-Through, Internet Streaming, Pay and Free Television, and ancillary media. (The term “television release” typically refers to all of pay TV, free TV, Video-on-Demand, and Internet Streaming.) The revenue generated from film rentals is approximately one half of that generated at the box office. (Ref. 12) The generation of revenue from non-box office sources is detailed in Section 10, Non-Box Office Revenue Streams.

Although the majority of theater box-office revenue is typically earned within the first weeks after the release of a motion picture, with such new markets additional income may continue to be generated for an indefinitely long period. Distributor expertise provides box office release strategy.

Production House

Upon securing the funding for the Motion Pictures, Producers shall seek a reputable, successful motion picture production company to effect the production of the Motion Picture. This shall include all the functions of a production house, including hiring crew and staff, hiring principal and non-principal actors, acquiring locations for filming, scheduling of shoot dates, purchasing liability insurance, performing post-production, obtaining domestic and foreign distribution, which may require contracting with a producers’ representative, and accounting.

Preliminary Casting

The following actors have expressed an interest in being cast, contingent upon the Motion Picture being funded, and are attached to the script: Anthony Crivello (www.imdb.com/name/nm0188266/) Polly Draper (www.imdb.com/name/nm0237164/) Rick Plastina (www.imdb.com/name/nm0686738/) Michael Wolff (www.imdb.com/name/nm0938292/)

The following actors are acquaintances of the Producers and have been contacted as of the date of the prospectus to ascertain their availability and whether they would want to become attached to the script: Armand Assante (www.imdb.com/name/nm0000800/) Lolita Davidovich (www.imdb.com/name/nm0000357/) Maria Dizzia (www.imdb.com/name/nm1978694/) John Mahoney (www.imdb.com/name/nm0001498/) Busy Philipps (www.imdb.com/name/nm0005311/) Charlotte Ross (www.imdb.com/name/nm0005383/) Jill St. John (www.imdb.com/name/nm0001762/) Robert Wagner (www.imdb.com/name/nm0001822/)

The agents of actors Ryan Gosling (www.imdb.com/name/nm0331516/) and Jim Sturgess (www.imdb.com/name/nm0836343/) have been contacted to express the Producers’ interest in their being cast in the lead role. We are familiar with the extended family of Jake Gyllenhaal (www.imdb.com/name/nm0350453/) and hope to present the script to him as well. Producers are currently working with Innovative Artists Agency of New York on principal casting.

Location Shooting

Many of the scenes in the Motion Picture will be filmed in a casino/resort complex, as detailed in Appendix F. These include scenes in the casino, hotel room, restaurant, entertainment lounge, lobby, and security office.

Other location filming includes the Buckingham Fountain in Chicago, Chicago’s lakefront, a neighborhood bungalow, and a university campus. The State of Illinois provides a tax credit equal to 30% of the costs of production which employ Illinois residents and companies. These tax credits can be sold and, as noted previously, typically earn 88% to 93% of their face value (Ref. 11). This consideration reduces the effective cost of production.

Proposed Schedule

Principal photography for the Motion Picture is to begin in winter year 1. It will be shot partially in Illinois and partially at a casino/resort complex, among other locations.

Development: May year 1 – September

Pre-production: September – December

Production: December year 1 – February year 2

Post-production: February – May

Begin Sales: May

Delivery: June

Fluidity of Concept

Neither the preliminary budget, the script, names of potential actors, the proposed schedule, nor other factors in the actual film shall be considered as immutable.

Historical Production Budgets and Revenues of Motion Pictures

Numerous scholarly studies of the motion picture industry by economists identify the risks and rewards of motion picture investment. Although revenue projections for motion pictures are difficult to make with any precision, these studies show that revenues depend most sensitively on the number of opening screens, the production budget, the presence of stars in the cast, audience guide rating (in order of increasing frequency, G, PG, PG-13, and R, the most commonly ascribed), and the genre, with additional secondary effects including critical reviews and whether the film is a sequel (Ref. 12, Ref. 13).

Production Budgets

Nash Information Services (Ref. 14) provides the production budgets, gross domestic box-office revenues, and gross foreign box-office revenues for 3629 American motion pictures dating from the early 20th century. In industry usage, “domestic” revenue includes receipts from the U.S.,

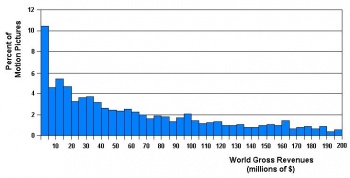

Canada, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Of those in the sample, only 25 motion pictures were released prior to 1940 and less than 100 were released prior to 1960. Accordingly, 97% of the motion pictures were released in the last 50 years. The distribution of the production budgets for the

3629 motion pictures is shown in Figure 1.

The mean production budget is $31.6 million, the median production budget is $19.0 million, and the standard deviation is $37.6 million. These figures demonstrate numerically the skewed quality of the distribution. Production costs of a relatively small number of large-budget motion pictures influences the mean value.

Because they are independent films, many of which are produced to provide exposure to new filmmakers rather than to secure profit for investors, the budgets and revenues of many of the low-budget films represented in this distribution are not comparable to the Motion Picture which is the subject of this Prospectus.

Revenues

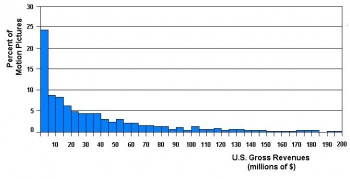

Of these 3629 motion pictures, gross domestic box-office revenues are provided for 3544 and gross worldwide box-office revenues, domestic plus foreign, are provided for 2329. The distribution of the domestic box-office revenues for the 3544 motion pictures for which the data is provided is shown in Figure 2.

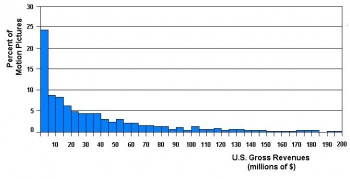

The distribution of the worldwide box-office revenue for the 2329 motion pictures for which the data is provided is shown in Figure 3.

The mean domestic gross revenues are $17.1 million, the median gross domestic revenues are $7.2 million, and the standard deviation of the gross domestic revenues are $16.2 million. The mean gross worldwide revenues are $17.1 million, the median gross worldwide revenues are $7.2 million, and the standard deviation of the gross worldwide revenues are $16.2 million. These numbers again demonstrate the skewed nature of these distributions. As with production costs, revenues from a relatively small number of motion pictures, the “blockbusters,” influences the mean value.

The cumulative figures are instructive. Of the motion pictures for which domestic box-office revenues are available, 67% equal or exceed $10 million, 52% equal or exceed $30 million, and 34% equal or exceed $40 million. Of the motion pictures for which foreign box-office figures are available, 85% equal or exceed $10 million, 75% equal or exceed $30 million, and 61% equal or exceed $40 million.

As an illustration of expected revenues for successful feature-length motion pictures, the table shows the gross domestic box-office figures for the top ten grossing motion pictures for the weekend of October 26 – October, 2012. Summer box office revenues are larger.

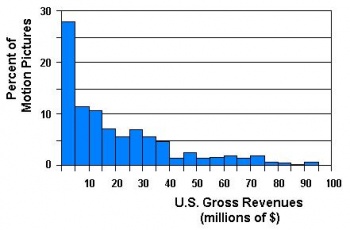

The distribution of gross domestic box-office revenues for the 493 motion pictures with a production budget between $10 and $15 million is shown in Figure 4. The median value is $14.2 million. An additional 27 data points exceed $100 million in value and are not shown in the figure. Of the these motion pictures, 61% of the domestic gross box-office revenues equal or exceed $10 million, 43% equal or exceed $30 million, and 20% equal or exceed $40 million. These selected cumulative figures are summarized in the table.

Dependence of Revenues on Number of Opening Screens and Production Budgets

Scholarly studies have attempted to determine the dependence of revenues on the two parameters to which it is most sensitive, the production budget and the number of opening screens (for example, Ref. 12). Although the spread of revenues as a function of both parameters is large, this analysis of figures for 2000 motion pictures indicates that the dependence on both parameters is strong. Statistically, revenues double between production budgets of $4 million and $12 million, for example, all other factors remaining constant. This interval includes the projected range of production budgets for the Motion Picture. Analysis also indicates that the dependence of revenues on the number of opening screens is strong. Statistically, revenues increase by a factor of four between 500 and 1500 opening screens, for example, all other factors remaining constant. This is an even stronger dependence than the dependence on the production budget.

These dependences are not independent. Large-budget motion pictures, with concomitant large marketing budgets and the presence of stars, may make showing the motion picture more attractive to exhibitors. This can at least partially explain the stronger dependence of revenues on the number of opening screens than on the production budget.

Effect of Star Casting

Although one might at first glance feel that the association of stars with a motion picture would significantly increase net revenues, the situation is a bit complex. A star is an actor, director, screenplay writer, or producer so listed on various Hollywood lists. About 20 to 40 feature-length motion pictures are released annually featuring one or more stars.

A scholarly study analyzing 2000 motion pictures (Ref. 13) concludes that the presence of most stars do not have a statistically significant association with a motion picture becoming a hit and earning large gross revenues. Less than twenty stars were found to have such an association.

Any association results from several factors. First, stars attract, and are attracted to, better scripts, with the consequent better chance for good reviews. Similarly, stars are attracted to motion pictures with large production budgets. Exhibitors, both domestic and foreign, may be more willing to show motion pictures with stars, with the promise of significant box-office receipts. Box-office receipts increase greater than proportionally to the number of opening screens. As noted, this might result from the presence of stars leading to this willingness of exhibitors to show such motion pictures.

On the other hand, salary demands of stars, as large as many millions of dollars, add significantly to the production budget. As a result, gross returns rather than revenues are of interest and analyzing those results show that motion pictures with stars are not statistically more successful than motion pictures without stars (Ref. 13). Others reach the same conclusion (Ref. 15).

In any case, casting of one or more of the high-salaried stars whose presence is strongly statistically related to significant revenue increases is not anticipated for the Motion Picture.

Effect of Rating, Genre, and Sequel

The Motion Picture is expected to obtain a rating of PG-13, the most frequently provided rating. It lacks violence and overt sexual content, but the subject matter is gambling. The genre is “drama.” The Motion Picture is not a sequel and is not expected to generate a sequel of its own. Because none of these features can be altered during production, they do not provide a strategy to generate revenues. Nonetheless, as described in Section 4, Gambling and the Gambling Movie Genre, over 125 motion pictures have been produced in the popular gambling genre and a number have become blockbuster successes.

Implied Production, Marketing, and Distribution Strategy

With these analyses in mind, the Producers will seek distribution of the Motion Picture in domestic and foreign theatres (see analysis of foreign distribution below in Section 10. Sources of Non-Box Office Revenue) with an emphasis on the number of opening screens, and casting of stars in both principal roles and in cameo roles at minimum cost.

Finances

Principal Risks

Investment in motion pictures is a high-risk venture. You may lose money by investing in the Motion Picture. Your investment is not a deposit in or obligation of, or guaranteed or endorsed by, any bank, and is not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve Board, or any other agency of the United States government or any agency of any state.

Because investing in motion pictures is speculative and risky, this investment opportunity will be offered only to accredited investors, as defined by Regulation D of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Regulation D requires, a) a minimum net worth exceeding $1 million at the time of the investment, not to include the value of the investor's primary residence, or an income exceeding $200,000 in each of the two most recent years or joint income with a spouse exceeding $300,000 for those years, and b) a reasonable expectation of the same income level in the year in which the investment is made. Investors must be able to afford to lose a significant portion or all of their investment without negatively affecting their lifestyle.

Because this investment opportunity is being directed solely to or through acquaintances, it need not, and is not, currently registered with the SEC or with the regulatory agencies of any state. The Producers make no representations as to the tax consequences of any investment losses and investors shall be responsible for obtaining legal and tax advice from professionals of their own choosing.

The sharing of profits with Investors will occur only if the total revenues generated by the distribution in domestic and foreign theaters, and sale of rights for television broadcast, reissue on electronic media, and ancillary sources as described in Section 10, Sources of Non-Box Office Revenues, exceeds the production budget.

Although production budgets are designed in good faith with best estimates, cost overruns resulting from labor disputes, overtime pay, and acts of God may occur.

The investment is subject to management risk in that the director and production staff make creative decisions. Both the director and production staff include cost considerations in their creative decisions but there can be no guarantee that these decisions will not lead to costs exceeding preliminary production budget and thereby erode profits.

Profits may in addition be adversely affected by a) the release of a motion picture starring the same lead actors, b) the release of a motion picture in the same genre, c) a national economic downturn affecting leisure spending, d) adverse publicity concerning lead actors, e) a Screen Actors Guild or teamsters strike and consequent picketing of movie theaters, f) an act of violence occurring at a movie theater leading to a reduction in movie attendance, g) a proliferation of pirated electronic versions of the motion picture, and other unforeseen circumstances.

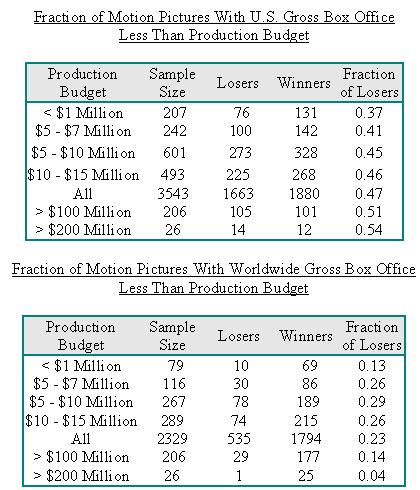

Risk Quantitative Analysis and Considerations

Investments in motion pictures are risky, but we believe that the degree of risk is overstated by those who have not analyzed the actual returns on investment. Utilizing the Nash database of motion picture production budgets and gross box-office revenues, when only gross revenues from theatrical distribution in the U.S. are included, the risk increases with the size of the production budget, as shown in the table. For motion pictures with a production budget exceeding $100 million, a greater than 50% chance exists that U.S. gross revenues in theaters will not cover the budget. This highly conditional finding is the only substantial evidence for the often-quoted statement that "more than 50% of all motion pictures lose money for their investors."

The results, however, change markedly when foreign distribution is included in the gross revenues, as shown in the second table. Motion pictures in all ranges of production budgets will, of course, become more profitable with the additional source of revenue. The fraction of motion pictures that lose money is halved, from 47% to 23%, when foreign distribution is included.

The monotonic increase in risk seen when only U.S. gross revenue is considered no longer exists. Indeed, now the most expensive motion pictures incur the least risk. This is understandable. The high budget, blockbuster motion picture is developed to appeal to audiences worldwide. The production budgets of such motion pictures include large amounts for marketing in Europe, Asia, and South and Central America as well as in the United States and Canada, cast several major stars, and will therefore attract multiple distributors and numerous exhibitors.

In the range of production budgets from $10 to $15 million, the fraction of motion pictures that gross less than their production budget decreases from 46% to 26% when foreign box-office revenues are included in the gross. A 74% chance exists, based on previous motion pictures and without including non-box office revenues, that a motion picture in this production budget range will be profitable. Details of these calculations are provided in the tables.

In the electronic media age, non-box office revenues are substantial. One scholarly reference states that revenues from video rental alone in the United States are 50% of domestic box-office revenues (Ref. 12) for motion pictures that become so available.

Sources of Non-Box Office Revenues

Approximately 50% of the revenue from a feature-length motion picture results from distribution through non-box office outlets. These include DVD/Blu-ray, Video-on-Demand, Electronic Sell-Through, Internet Streaming, Pay and Free Television, and ancillary media. As a result, motion pictures can be distributed for an indefinite length of time domestically and internationally through retailers and various electronic media. Although the majority of theater box-office revenue is typically earned within the first weeks after the release of a motion picture, with such new markets additional income may continue to be generated for an indefinitely long period.

DVD/Blu-ray The majority of DVD/Blu-ray revenues are generated from sales in retailers such as WalMart, Target, and Best Buy, as well as online vendors such as Amazon and DVD Empire. Firms such as Netflix, Redbox, and Blockbuster provide additional revenue by purchasing a substantial number of units for rental at the early high-price points.

Video-on-Demand Video on Demand allows consumers to rent a one-time viewing of a film without the use of an electronic device such as a DVD or videocassette player. “Premium” VOD has a short window of accessibility, almost immediately after or even during the theatrical release, in which case a higher fee is charged. “Standard” VOD is available later at a reduced rate. In both cases, suppliers include all cable and satellite TV companies as well as multi-operational platforms such as PlayStation and Xbox.

Electronic Sell-Through (Digital Download) Digital download or electronic Sell-Through allows the consumer to download a film onto his or her computer, tablet, smartphone, or PDA device for unlimited use for unlimited time for a fee less than the cost of purchasing a DVD. Many firms are involved in this rapidly growing method of film distribution including Amazon and iTunes.

Internet Streaming With Internet Streaming, the newest form of digital distribution, consumers can view a film in real-time on their televisions, computers, gaming systems, and mobile devices for a monthly fee. Leaders in this field include Netflix, Hulu, and Google, with numerous other firms expected to be coming online soon.

Pay and Free Television Pay Television sales typically begin nine months after the initial release of a motion picture. For a monthly subscription fee, premium cable channels such as HBO, Showtime, Starz, and Cinemax provide consumers with films prior to their showing on network or basic cable stations. Although exceptions exists, pay TV agreements generally produce revenues in the tens of thousands of dollars. The major source of revenue from such agreements is commercial advertising. Free television buyers include the networks, including CBS, NBC, ABC, FOX, TNT, USA, and AMC.

Ancillary Media Films can be distributed through many additional platforms. Ancillary media includes in-flight, educational, military, prisons, hotels, and cruise ships. While this demand is limited, it is a potential significant additional source of revenue.

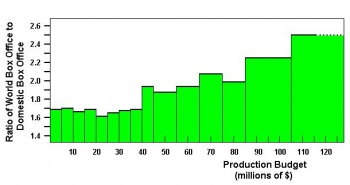

Foreign Sales Foreign box-office revenue constitutes a significant portion of worldwide box-office receipts. Figure 3 displays the revenues for the 2329 motion pictures in the Nash database for which foreign box-office receipts are reported.

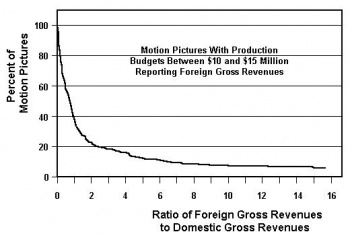

Details of these figures are instructive. Figure 5 displays the percent of motion pictures for which the ratio of foreign gross box-office revenues to domestic box-office gross revenues is at least a given value. The 50% mark, designating the median value of this ratio, occurs at a value equal to 0.87. This corresponds to foreign sales contributing approximately 47% of the total worldwide box-office revenues of a film.

A value of the ratio equal to unity indicates that the total gross box-office receipts are doubled and a value of the ratio equal to two indicates that the total gross box-office receipts are tripled with the addition of foreign distribution, for examples.

Similarly, Figure 6 displays corresponding results for the 289 motion pictures in the database with production budgets between $10 and $15 million. The contribution of foreign receipts is even more striking for these motion pictures. The 50% mark, designating the median value of this ratio, occurs at a value equal to 0.68. This corresponds to foreign sales contributing approximately 40% of the total worldwide box-office revenues of a film.

Examination of these figures shows that larger fractions of motion pictures with production budgets in the range of $10 to $15 million, compared to all motion pictures, obtain significantly larger fractions of their gross box-office revenues from foreign distribution. Including foreign box-office revenues leads to the worldwide gross revenues at least doubling for 44% of all motion pictures and 46% of the motion pictures with these moderate production budgets. (In other words, about 44% of all motion pictures that report foreign gross revenues have at least equal gross box-office receipts from foreign distribution as from domestic distribution.) Including foreign box-office revenues leads to the worldwide gross revenues at least tripling for 18% of all motion pictures and 24% of the motion pictures with these moderate production budgets. As a final illustration, including foreign box-office revenues leads to the worldwide gross revenues at least quadrupling for 10% of all motion pictures and 19% of the motion pictures with these moderate production budgets.

This trend of larger percentages of the moderate production budget motion pictures than of all motion pictures exceeding a given multiple continues at all higher multiples. With such considerations, obtaining significant foreign distribution is a major strategy of the Producers.

This strategy requires marketing overseas. More than 50 foreign territories are targeted by motion picture producers, including ten so-called major foreign territories of which Japan and Germany are the largest. Sales representatives promote motion pictures at international markets and events, including those in Cannes, Berlin, and Toronto, and at trade shows such as those of the National Association of Television Program Executives (NAPTE), MIPCOM, and American Film Market (AFM).

The contracts to obtain foreign distribution within the territories usually have several characteristics. Normally, “all media” rights, including theatrical, electronic, and ancillary, are sold to a single buyer within a territory. The contract includes an advance, which is typically paid to the production company in two portions, upon signing and upon delivery of the motion picture. As with contracts in the book publishing industry, additional revenues are paid to the production company if sales exceed the amount of the advance. The sales representative receives a sales commission from the gross receipts. The security of the foreign revenues are ensured by their being deposited in accounts controlled by a third party.

The Nash database does not provide or attempt to estimate difficult-to-obtain revenue figures for sources other than theatrical box office. These additional sources are increasingly significant sources of revenue as computer and telecommunication innovations are introduced to the modern movie-going public. With such sources of revenue other than box office, modern motion pictures have greater changes of exceeding the production budget than in prior decades. The Producers will vigorously seek distribution through these various modes of non-box office revenues.

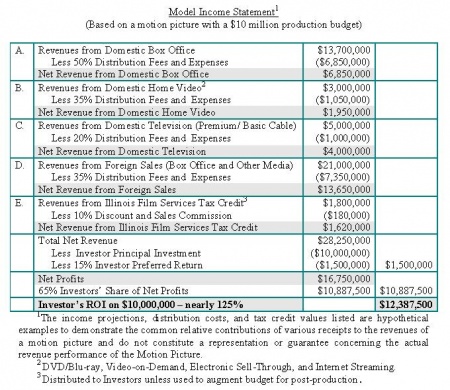

Model Revenues

To obtain an idea of the relative contributions of these various modes of revenue generation, we present a model of typical relative amounts of revenues. These are hypothetical figures for a $5 million production budget motion picture and are presented to demonstrate the common relative contributions of non-box office receipts to the cash flow of a motion picture. The gross revenue reported for domestic box office is the $13.7 million median value quoted for motion pictures with production budgets between $10 and $15 million as quoted in Section 7.b, Historical Production Budgets and Revenues of Motion Pictures, Revenues. The gross revenue reported for foreign box office is the sum of the similarly reported median value and an estimated $8 million for revenue from electronic media. The figures provided do not constitute a representation or guarantee concerning the actual non-box office performance of the Motion Picture.

1-The income projections, distribution costs, and tax credit values listed are hypothetical examples to demonstrate the common relative contributions of various receipts to the revenues of a motion picture and do not constitute a representation or guarantee concerning the actual revenue performance of the Motion Picture. 2-DVD/Blu-ray, Video-on-Demand, Electronic Sell-Through, and Internet Streaming. 3- Distributed to Investors unless used to augment budget for post-production.

Profit Sharing and Accounting

Distribution of Excess Funds

If the total amount of funds raised for the production of the Motion Picture is less than the actual money spent in production of the Motion Picture, those excess funds shall be reimbursed pro rata, without interest, to the Investors no more than six (6) months after the opening screening of the Motion Picture.

Distribution of Profits

Net profits will be distributed to Investors on a pro-rata basis. Accounting will be made annually in April for the preceding calendar year, and payments due the Investors will be remitted thereafter in U.S. dollars. The Producers agree to render a statement of account to the 30th day of April immediately following the opening screening of the Motion Picture and thereafter similar statements for all periods during which revenue from the Motion Picture have been received by Producers and to send such statements, together with payment of the amount due thereon, on or before the 31st day of May. If in any period the total payment due to the particular Investor is less than five hundred ($500) dollars, the Producers may defer the rendering of a statement and payment until such time as the sum of five hundred ($500) dollars or more shall be due. Upon the Investor’s written request, the Producers shall render a detailed statement which shall include the revenues from all sources, including foreign distribution.

Examination of Accounts

Financial reports will be prepared and distributed to the Investors by the accounting firm retained by the Producers for that purpose. A certified public accountant designated by the Investor may inspect the Producers’ books and records, insofar as they relate to the Motion Picture, no more than once a financial quarter during normal business hours upon written request in order to verify the accuracy of the Producers’ statements issued in respect to the Motion Picture. If an error is discovered as a result of any such examination, the party in whose favor the error was made will promptly pay to the other the amount of the error without interest.

Payments to Financial Intermediaries

All investments are sent directly to the Producers. No intermediary exists, no fees are imposed by intermediaries, and no potential conflict of interest exists resulting from an intermediary directing investment in the Motion Picture as opposed to other investment vehicles.

Taxes and Tax Benefits

Proceeds to Investors are generally taxable as ordinary income, unless the Investor is investing through a tax-deferred arrangement, such as a 401 (k) plan or an individual retirement account.

Section 199 of the Internal Revenue Code allows producers and investors to receive under certain circumstances a 9% deduction. A second relevant portion of the Internal Revenue Code, which had expired at the end of 2012, has been renewed as part of the American Recovery Act. Section 181 states that investment in a motion picture filmed in the United States is 100% tax deductible for the investor in the year of investment. Unlike other investment vehicles, the deduction is not contingent on loss. The total amount invested is deductible independent of the outcome of the investment. These effectively reduce the tax rate on qualified production activities income (QPAI), which includes profits and/or other taxable income resulting from domestic motion picture production.

The Motion Picture is eligible for the Illinois Film Services Tax Credit, worth 30% of all qualified in-state expense. The tax credit is transferable and can be divided into ten transferable portions. If the Investor has no need for the Illinois tax credit himself, the credits can be sold. They are typically sold for at least 87.5 cents on the dollar. The proceeds can be collected from the State of Illinois approximately three to six months after the completion of principal photography.

This tax credit is effectively additional revenue for the Motion Picture, which the Producers may use to augment the Motion Picture budget in post-production or, if not needed for that purpose, distributed to Investors in proportion to their principal investment. (If Investors have taxable income in Illinois, 100% of the credit could be directly transferred to offset said income, again in proportion to their principal investment.) Similar considerations apply to motion pictures filmed in Canada.

As a result of the 100% federal deduction and the 30% Illinois tax credit, various scenarios can be developed. These are shown in the table.

For example, take an Investor who invests $10 million in the Motion Picture. If the Investor is in the 20% federal income tax bracket and if 50% of the production budget is spent in Illinois, then the effective investment is only $6.5 million. As a result, the revenues need only amount to 65% of the costs of the Motion Picture for the investor to begin earning a profit.

Disclaimer and Governing Law

Producers warrant that all information provided in this Prospectus is true and accurate to the best of their knowledge. Regardless of the place of its physical execution, this Prospectus is made under, and shall be governed by and construed according to, the laws of the State of Illinois, United States of America, without regard to that state’s conflicts-of-law principles. Any action with respect to this Prospectus may only be brought and maintained in the federal or state courts in Cook County, State of Illinois, United States of America. The parties consent to jurisdiction of any such court.

Nothing in this Prospectus shall be construed to imply any guarantee of a return on the investment to the Investor. This Prospectus need not be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission or any other government agency, and has not been so filed.

Confidentiality

This Prospectus has been prepared by the Producers and is intended solely for persons receiving it as potential Investors in the Motion Picture. The information contained herein is strictly confidential, proprietary, non-public, which is not authorized for any reproduction or distribution and shall not be disclosed to anyone other than representatives of the original recipient for the sole purpose of evaluating this offering.

This document does not constitute an offer or solicitation in any jurisdiction in which such an offer or solicitation would be unlawful. No person has been authorized to give any information or to make any oral or written representations concerning the Producers or this offering other than that contained herein. If such is given, that information or those representations cannot be considered as originating from the Producers.

The recipient of this Prospectus acknowledges compliance with the above.

Entire Prospectus

This Prospectus constitutes the complete and entire Prospectus between the Producers and the Investors. Waiver or modification of this Prospectus will require the Producers to issue a new prospectus.

Financing Model and Full Prospectus

Funding models based on federal and state law production incentive are presented at en.wikisage.org/wiki/Never_Split_Tens

Additional material about Never Split Tens appears at en.wikisage.org/wiki/Never_Split_Tens_(movie)

Appendices

Appendix A. Tagline, Logline, and Synopsis

“Never Split Tens” aka “Doubling Down”

Tagline: An M.I.T. professor develops a winning system for the game of blackjack.

Logline: When a driven M.I.T. mathematics professor develops a computer system for winning at the card game blackjack, he jeopardizes his career, marriage, and physical well-being, but attains worldwide celebrity by winning large sums in casinos from Nevada to Puerto Rico and discovers peace and a renewed commitment to his career and marriage. Based on the life story of Professor Edward O. Thorp. When a driven professor develops a computer system for winning blackjack and tests it with mob-backed money in casinos, he loses his wife and job but redeems himself and attains peace when his huge winnings cause a revolution in the casino industry. Based on a true story. No efx. When a driven professor develops a computer system for winning blackjack and tests it with mob-backed money in casinos, he jeopardizes his career, marriage, and physical well-being, but redeems himself and attains peace when his huge winnings cause a revolution in the casino industry. Based on a true story. No efx.

Synopsis

“Beat the Dealer” is based on the true story of Professor Edward Oakley Thorp, the American mathematician who gained worldwide renown by showing mathematically that the game of “21” could be beaten, thereby making it the most popular casino game and revolutionizing the casino industry. As a mathematics graduate student at UCLA, THORP devours a scholarly article about mathematical simulation of the game of 21. His advisor cautions Thorp that “you can’t get rich doing mathematics.” With the moral support of fellow UCLA math graduate student ALLAN WILSON and Thorp’s wife VIVIAN, whom Thorp had met as musicians at a collegiate jazz festival, Thorp successfully defends his Ph.D dissertation. He obtains a prestigious position in mathematics at M.I.T. but irritates his colleagues by presenting a paper on his electronic computer simulations of 21 at an American Mathematical Association meeting in Washington D.C. A front page article in the Boston Globe leads to t.v. appearances on “What’s My Line,” “To Tell the Truth,” and “Truth or Consequences.” Mobster and bookie MANNY KIMMEL contacts Thorp and offers to bankroll him on a trip to Nevada casinos. They seal the deal during dinner at Vivian’s and Thorp’s home. The Thorps, Allan, Thorp’s computer programmer friend, JULIAN BRAUN, and Manny travel to Reno to test Thorp’s system. The association with Manny, Vivian’s concern that Thorp devotes too much time to his gambling experiments, and Manny’s insulting behavior toward Julian, lead Vivian to return to California and two careers as a designer and jazz singer. Thorp travels to Lake Tahoe with Manny and proves the power of his system by continuing to generate large profits for his mobster bankroller. Casinos, aware of Thorp, bar him from playing and Thorp and Manny hire a Hollywood make-up artist to create a disguise. Thorp’s continued profits lead to threats and physical attacks. A trip to the casinos of Puerto Rico with Manny convinces Thorp that the system he developed works even at casinos with rule variations. The experiment successfully completed, Thorp travels to San Francisco and attends Vivian’s show at the famous Dick’s at the Beach nightclub in Golden Gate Park. During a performance of their favorite song, “I’ve Never Been in Love Before,” Thorp pulls out his trumpet and from the back of the dimly-lit club plays riffs accompanying Vivian’s vocals. Recognizing Thorp’s trumpet sounds, Vivian runs to the back of the club and they embrace in reconciliation. Happily back in academia at the University of California at Irvine and family life, Thorp discovers a mathematical system for playing the stock market. This system will eventually lead Thorp to earn tens of millions of dollars as the first hedge-fund manager, proving that “you can get rich doing mathematics.”

Appendix B. Principal Profile -- Leslie M. Golden

Les Golden (screenplay writer; co-producer) is an actor, stand-up comedian, jazz musician, writer, cartoonist, astronomy/physics professor, and professional card-counter. His writing is heavily influenced by his extensive work with Del Close, the improv guru of Chicago’s Second City improvisational nightclub. His Laboratory Exercises in Physics for Modern Astronomy was published in November, 2012, by Springer New York and, based on his work with Close, he received a contract from Bantam/Doubleday to write The Scientific Approach to Creativity: The Techniques of the Chicago School of Improvisational Theatre.

A graduate of Cornell University in engineering physics and holding the Ph.D from the University of California, Berkeley, in astrophysics, he has won numerous writing awards, including first prizes in the Eric Hoffer and Lili Fabilli Laconic Essay Contest, the International Compuserve Magazine Essay Competition, and the Senior Division of the Nicolaus Copernicus International Essay Competition.

In addition to being a professional card counter, he has taught probability and statistics at the graduate student level and published “An Analysis of the Disadvantage to Players of Multiple Decks in the Game of 21” in the June, 2011, issue of the peer-reviewed journal The Mathematical Scientist. He applies probability and statistics to popular casino games as a columnist for four London-based gambling magazines. His paper, “An Empirical Analysis of the Risks and Rewards of Motion Picture Production,” has been submitted to the peer-reviewed Journal of Cultural Economics. Mr. Golden is a member of Phi Beta Kappa (arts and sciences honorary), Tau Beta Pi (engineering honorary), Pi Delta Epsilon (journalism honorary), the Screen Actors Guild, and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

Training

Del Close, Chicago, Second City, Improvisation Don DePollo, Chicago, Second City, Improvisation Ann Woodworth, Northwestern University, Acting Lowell Manfull, Penn State University, Playwriting Henrik Eger, Delaware County Community College, Screenplay Writing

Produced Scripts “The Skull Caper” – One Act Comedy “Murder by Mistletoe” – Two Act Murder Mystery/Comedy “Tapioca Café” – Half-hour Television Comedy Pilot

Appendix C. Glossary and Explanation of Terms

Gross Revenue – All receipts from viewers of the motion picture in any media paid to exhibitors and third-party buyers.

Distributors’ Gross Revenue - All money paid to domestic and foreign distributors by exhibitors and third-party buyers for the commercial rights to show the motion picture.

Producer’s Net Revenue - The remainder of the distributors’ gross revenue paid to the producers after deduction of the distributors’ sales commissions, marketing costs, fulfillment costs, and guild residuals.

Net Profits – Remainder of the producer’s net revenue once investors have been paid 115% of the investors’ principal investment. These net profits are typically split 50/50 between the investors and producers (for the current Prospectus, the split is 65/35, with the investors obtaining the 65% share). All third-party participations are paid out of the producer’s share.

Distributor - The individual or firm, both domestic and foreign, that presents and sells the rights to show a motion picture by an exhibitor or a third-party buyer.

Exhibitor – The proprietor of a movie theater, both domestic and foreign.

Fulfillment Costs – Costs incurred by the distributor and reimbursed to him from gross revenues for fulfilling his obligations to the producers, exhibitors, and third-party buyers. This includes creating copies of the motion picture, production of closed captioning, shipping, pen-and-paper or internet-based quality center (QC) reports for quality control, and all other contractual requirements of exhibitors and third-party buyers. Fulfillment costs are typically $10,000.

Guild Residuals – Costs incurred by the distributor and reimbursed to him from gross revenues for payment of residuals to actors, directors, and writers. These costs are equal to a percentage of gross revenue markets paid by the distributors to the Screen Actors Guild, the Directors Guild of America, and the Writers Guild of America, if members of those guilds are employed in the production of a motion picture. For actors represented by the Screen Actors Guild, the payments are 3.6% of the gross revenue plus handling fees.

Marketing Costs – Costs incurred by the distributors and reimbursed to them from gross revenues for marketing and publicity concerning the motion picture, including expenses related to attending sales conventions and the cost of promotional materials such as posters and trailers. Marketing costs are typically less than $35,000.

Sales Commissions – Payment to the distributors from gross revenues for finding, negotiating, and fulfilling deals with exhibitors and third-party buyers. Sales commissions are typically 10% of the domestic gross revenue and 20% of the foreign gross revenue.

Third-party Buyers – Individuals or firms who purchase a motion picture for showing in non-box office media such as DVD/Blu-ray, Video-on-Demand, and Electronic Sell-Through. These include entities such as Showtime and Redbox.

Third-party Participations – Portions of the net profits payable to various key contributors to the motion picture, including the director, principal actors, and writer(s).

Appendix D. The Game of 21

Blackjack, also known as 21, Vingt-et-un, and by other names, is a two-person card game in which the player tries to obtain a hand where the total numerical value of the cards exceeds that of the dealer without exceeding 21. More than two people can play, but each is playing against the dealer. The numerical value of the cards equal their face value, with all “face” cards having a value of ten. The player can choose the Ace to take a value of one or eleven.

After the bets have been placed on the table, limited to minimum and maximum amounts set by the casino, the dealer deals two cards, one card at a time, in turn to each player, taking his own cards last. The first card that the dealer deals to himself is dealt face down, and the second card and all subsequent cards that the dealer deals to himself are dealt face up.

If the two initial cards are any ten-value card and an Ace, the winner has achieved a “natural” or “blackjack”; he is then paid 1 1/2 times his bet and his play for that round is concluded. If the dealer also has a natural, the hand is a draw and no money changes hands.

The player has three decisions to make. Two of the decisions are available only after the first two cards are dealt. If the player is dealt two cards which are numerically identical, a “pair,” he has the option of “splitting” the two, and getting two hands. He then receives a new card for each of the split hands. If a pair is drawn on these second draws, he can split again, and can do so as long as pairs continue to appear. Some casinos limit the number of hands the player can split. A total allowance of four split hands is frequently encountered.

The second decision that is made only after the first two cards are dealt is “doubling down.” This can be done on any combination of cards. The player doubles his bet, but will only receive one additional card on the hand. The player can double-down on either or both of the split hands. After those initial decisions are made, the player may stand on his existing hand or receive an additional card or cards from the dealer.

The player can stand on any hand. The dealer must take additional cards until he reaches or exceeds 17, and must then stand. (In many casinos a dealer must take a hit if his total of 17 includes an Ace.)

The hands of each player are played in succession. Each player plays out his hand until he decides to take no further cards or his point total exceeds 21, in which case he is said to have “busted” and loses his bet. After every player has played out his hand, the dealer plays his hand. If the dealer busts, then all the players who remain in play win their bets. If the dealer does not bust, then the players with higher totals win their bets while those with lower totals lose their bets. No money is exchanged in the case of a draw. After all money has been exchanged, a new game begins with the dealer dealing two additional rounds of cards.

In the early 1960’s, Edward O. Thorp, in collaboration with computer programmers Julian Braun and Harvey Dubner, utilized electronic computing to devise a strategy for the game of 21. As a result of the publication and ensuing popularity of Thorp’s book, Beat the Dealer, what had been a relatively unpopular casino game has become the overwhelmingly most popular casino game.

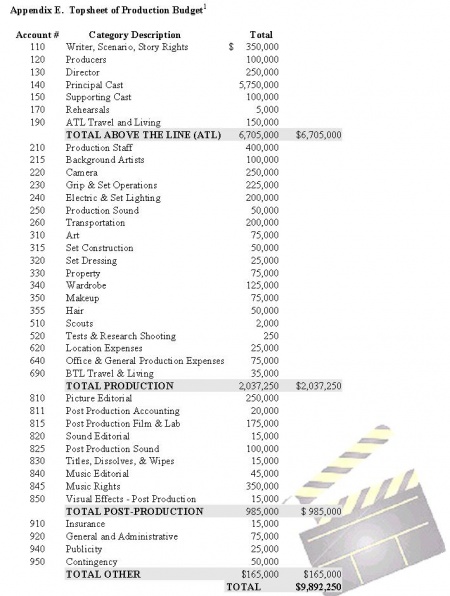

Appendix E. Topsheet of Production Budget

1-The figures are based on line-by-line analysis of the First Draft of the screenplay. The actual figures will change as a final shooting script is created, but are not anticipated to vary significantly from those presented here.

Appendix F. Casino Partnership and Marketing

The Producers wish to secure as a partner/investor in the production of the Motion Picture a casino/resort complex. Both the subject of the Motion Picture and many of its scenes involve casinos. It is therefore advantageous to partner with a casino in the production of the Motion Picture for mutual marketing and profit.

A significant fraction of the scenes occur within a casino facility:

• the casino: a craps table and a blackjack table • an entertainment lounge • the lobby • a restaurant • a hotel room • the security office

In return for partial funding of the projected production budget of $10 - $15 million, the casino would obtain the following considerations, among others to be negotiated:

1. Pro-rated profit-sharing return on investment after production expenses (“back-end participation”).

2. Location of numerous scenes; a major fraction of the Motion Picture would be shot in various locations throughout the casino facility. This would display the amenities of the facility to the theater-going public and to those who rent or view the Motion Picture in electronic format.

3. Regional media exposure over a period of more than one year, from pre-production through filming, post-production, theatrical release, and availability on rentals and electronic format. The exposure would include trade publications, newspapers, television, and radio.

4. Nationally-syndicated entertainment and talk-show television exposure.

5. Artifacts such as props, costumes, the actual screenplay, director’s script, autographed photographs of the principal actors, and others artifacts for placement in a museum at the casino as a tourist attraction.

6. Use of casino personnel as day-players, including acting instruction, in roles such as dealers, pit bosses, gamblers, and waitresses. We have found this generates significant goodwill among casino personnel who are suddenly “movie stars.”

7. Prominent screen credit that filming of the Motion Picture occurred at the casino.

8. Marquee stating words such as “Location for Filming of the Motion Picture Never Split Tens.” This generates traffic and interest as shown by the continuing popularity of the pool hall in Chicago where “Color of Money” was filmed.

9. Photos of the cast and of the filming process for placement throughout the casino as management deems fit.

10. If a hotel is available at the casino, the out-of-town actors would be housed there. The casino could rename such rooms as, for illustration, the "Tom Hanks Suite.”

11. Public casting calls for paid extras at the casino will generate traffic.

12. The marketing benefit continues as long as the Motion Picture is shown for rental or on electronic media. This typically results in exposure for 10 to 20 years.

13. Goodwill and intangibles.

Appendix G. Contact Information

Leslie M. Golden 934 Forest Avenue Oak Park, Illinois 60302 (708) 848-6677 drlesgo@aol.com

References

1. www.professionalgambler.com/right.html

2. www.locksmithsportspicks.com/super-bowl-how-much-bet

3. www.cnbc.com/id/29960655

4. http://www.dailyfinance.com/2012/03/27/who-are-the-nations-biggest-suckers-lottery- players/

5. http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_much_money_is_spent_on_gambling_each_year_in_US

6. http://www.igb.illinois.gov/annualreport/2011igb.pdf

7. http://www.indiangaming.org/info/alerts/Spectrum-Internet-Paper.pdf

8. www.casinospage.com/faqs.htm

9. govinfo.library.unt.edu/ngisc/research/lotteries.html

10. http://www.cnbc.com/id/34312813/Top_Sports_for_Illegal_Wagers

11. Personal communication, Illinois Film Office, August 8, 2012.

12. A. De Vany and W. D. Walls. “Uncertainty in the movie industry: Does star power reduce the terror of the box office?” Journal of Cultural Economics, November 1999; http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1007608125988

13. W. D. Walls. “Robust analysis of film earnings.” Journal of Media Economics, vol. 22, no. 1, pages 20-35, 2009; http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08997760902724662

14. http://www.the-numbers.com/movies/records/allbudgets.php

15. Ravid, S. A. (1998). Information, blockbusters and stars: A study of the film industry. Working paper, New York University.